“Kafka’s works never cease to beguile us”

18 Mar 2024

Why it is worth reading Kafka and what sets the writer apart: An interview with literary scholar Oliver Jahraus.

18 Mar 2024

Why it is worth reading Kafka and what sets the writer apart: An interview with literary scholar Oliver Jahraus.

A hundred years ago, on 3 June 1924, Frank Kafka died at the age of just 40. An interview with Oliver Jahraus, Professor of Contemporary German Literature and Media at LMU.

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from troubled dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a horrible beetle.” This is the sentence with which Kafka begins his story The Metamorphosis. As a literary scholar, what do you say to this opening?

Oliver Jahraus: It is one of the most magnificent opening lines in world literature. It contains the signal word “beetle” [translator’s note: also rendered in different English translations of Kafka’s work as “vermin”, “cockroach” or simply “gigantic insect”]. On the one hand, this piques the imagination: How are we to envisage a human being transformed into a beetle? Yet the reader also quickly notes the social connotation: It is a drastic put-down, a very nasty insult that clearly has a role to play in this family. That in turn opens up a new angle on the question of how the characters deal with the situation, and why a member of the family is suddenly transformed in this way. In this one sentence, we also see what a remarkable storyteller Frank Kafka was: Read these few words and you can’t put the story down.

Kafka transcends the time in which he wrote, identifying problematic issues of the modern age that, regardless of all debates about postmodernism and post-postmodernism, remain relevant today.Oliver Jahraus

Kafka died a hundred years ago. Why is it still worth reading him?

There are several reasons. Looking back across the sweep of literary history, he was definitely a man of his day. But that is never the whole story. Kafka was extremely well informed and read many literary journals. You could say that Expressionism was predominant, and there are clear lines connecting Kafka to his literary milieu. But there is more to Kafka than that: There is the way he told his stories. And there are the topics he addressed – topics in which the critical elements of modernity come to the fore. Power within a social construct is one example; another is the issue of how the individual is recognized by his environment and society.

There is also a religious undertone: Does religion – in Kafka’s case, the Judaism with which he had a troubled but intense relationship – give us answers to the question of how people are to be recognized? Kafka transcends the time in which he wrote, identifying problematic issues of the modern age that, regardless of all debates about postmodernism and post-postmodernism, remain relevant today.

Why did Kafka of all people do this so well?

Modernity is characterized by exceptional social complexity. How do we grasp this complexity? What is our experience of it? Around the year 1900, modernist introspection was a big thing among the intellectual circles in London, Paris and Berlin, but also in Munich, and of course in Vienna. Vienna was a key point of reference for Kafka, but its influence also extended to Prague, a pivotal bastion of culture in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. None of these descriptions do justice to the complexity of the world, however. And that is where Kafka comes in, finding his very own way of transforming such issues into narratives.

There are always two aspects: He is telling a story, yes: The narrative element is hugely important. But he is also making a diagnosis. Both aspects are interlinked in his writings.

What do we need to know about Kafka’s life to understand this diagnostic ability?

Kafka’s life situation may have predestined him for this role. He came from a Jewish family that had trod a path of assimilation that is far from easy – a path, if I may sum it up very broadly, from Eastern European Jewry, which was still heavily steeped in traditional ideas, rituals and convictions, to a Western form of Jewishness that was shot through with assimilation. Normally, you would expect such assimilation to gravitate toward the social majority, i.e. the Czech population. In the case of Kafka and his family, however, it involved assimilating with the culturally significant class that itself was a minority: the Germans. This obviously had to do with the predominantly German-speaking nature of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. And it led to all kinds of ructions.

As an author writing in German, Kafka belonged to the Germans; but precisely as a Jewish author, he did not. Nor did he fully belong to the Jewish community, because he had discarded many Jewish traditions, although he later did expect Jewishness to afford him a measure of self-affirmation. All these factors together are deeply symptomatic of what makes Kafka a modernist, and of the author’s awareness of all that is problematic about the modern era.

Kafka could not have anticipated the terrifying scale of the cultural rift that the National Socialists would unleash upon the world in the shape of the Holocaust. But he sensed something else: He sensed that there is a darker side to the modern era.Oliver Jahraus

Kafka was a lawyer and civil servant. He wrote his literary texts in his spare time. | © IMAGO / agefotostock / Universal Images Group Sovfoto / UIG

Some of Kafka’s works are very dark, even brutal. From a present-day perspective, you might say he portended the terror and violence of wars and the Holocaust.

I would be very careful about saying that. Kafka could not have anticipated the terrifying scale of the cultural rift that the National Socialists would unleash upon the world in the shape of the Holocaust. But he sensed something else: He sensed that there is a darker side to the modern era. If we look at this in Kafka, it begins relatively harmlessly as the modern era is accompanied by immensely bloated bureaucratization. That in itself is nothing bad. It is something that could bring about justice, because everything is assessed in the same way. However, when this kind of bureaucracy suddenly turns in on itself and becomes an end in its own right, what emerges is a sort of meta-bureaucracy that no longer knows what it is actually there for.

How does Kafka tackle this issue? Do you have an example?

He does it in his novel The Castle, for instance. Imagine a small village where people live, and above them towers a huge castle – an authority containing lots of individual chambers, each of which is in turn subdivided into various hierarchic levels that churn out mountains of files. You ask yourself: Who administers this gargantuan castle bureaucracy, given the tiny village for which it is responsible?

Reading the novel from a slightly more detached perspective, it clearly paints a picture of bureaucracy and bureaucratic decisions in general. And then aspects of violence come into the picture. It is not just dysfunctional, but at the same time suffused with eroticism. It is a sado-masochistic game. This is most blatantly apparent in Kafka’s story In the Penal Colony, where a method of torture – used as part of the criminal procedure – is described in every gory detail. The link between such unrestrained delight in violence on the one hand and bureaucracy on the other hand gives us an idea of the negative potential inherent in these processes of modernization.

As a lawyer, Kafka had an insight into administrative activity and bureaucracy, with all its hierarchies, delineated competencies, files, statements – and the way it dealt with cruelty.Oliver Jahraus

Did Kafka see the darker side of bureaucracy so clearly because he himself was a lawyer?

In principle, I would agree with that. As a lawyer, he had an insight into administrative activity and bureaucracy, with all its hierarchies, delineated competencies, files, statements – and the way it dealt with cruelty. He sat at the critical juncture. He repeatedly had to read and write reports detailing individuals who had suffered cruel fates due to accidents at work. In his position, he took care of improving structures in order to reduce the number of insured events for the large, semi-nationalized occupational accident insurance institution for which he worked. He thus had an insight into the violent forces of life and how bureaucracies dealt with them.

On a personal level, Kafka was described by friends of both sexes as gentle, good, shy and a lover of truth. How does that fit in with what he wrote?

The author Louis Begley took one quote from Kafka and used it as the title of his book, The tremendous world I have inside my head. In his immediate dealings with people, Kafka was extremely obliging. The mythical notion of a lone wolf surrounded by gloom is not true. He was someone who enjoyed life. Socially, he was wonderfully integrated and had many friends. And he also had the one friend – Max Brod – who stood by him long after Kafka himself had passed away. Kafka was also a womanizer. He socialized easily with women and relatively quickly channeled this ability into one area where he was in perfect control of the situation: writing and correspondence.

Yet he also had an eye for the wider world – and perceived the monstrous in what he saw. This was the driving force behind his writing. So, there is the nice Kafka, the Kafka with monstrous fantasies and the difficult Kafka. It is true, he was a difficult person. Witness the wicked game he played, while feigning to be in love, with his fiancée Felice Bauer. He used Felice Bauer – not as a woman, but as a mail address. As his fiancée, he cruelly kept her waiting. Yet his letters to her are a masterpiece in their own right.

Max Brod and Franz Kafka epitomize a unique example of friendship.Oliver Jahraus

Kafka and Brod met during Kafka's studies and were lifelong friends. | © picture alliance / dpa | Daniel Bockwoldt

What part did his friendship with Max Brod play in Kafka’s work?

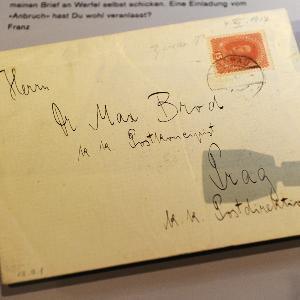

To have had this friend was incredible in many respects. Max Brod and Franz Kafka remained close throughout their life, as attested by their mutual correspondence even though they constantly saw each other. When Kafka felt he was nearing death, he penned two wills. He specified that everything he had written was to be destroyed by Max Brod. Yet Brod was the only person of whom Kafka could be sure that he would not comply with this instruction.

Though himself an author, Brod placed his whole existence in Kafka's shadow and strove to make his friend famous. Kafka had published relatively little during his lifetime. Without Max Brod, we would not have the Kafka we know today. So, we see a friend who really did everything to preserve his friend’s literary legacy and make it accessible to posterity. On a human level, I find that very moving. Max Brod and Franz Kafka epitomize a unique example of friendship.

With Kafka, you learn what literature can really achieve.Oliver Jahraus

Professor Oliver Jahraus | © LMU

You have just published a book about Kafka. What is it that fascinates you about this author?

What fascinates me is that, with Kafka, you learn what literature can really achieve. If you needed to make it clear to someone what literature is for, what function it serves, how it can do so and how intensively it can do so – which is my job as a university lecturer in literary science – then I would give the person a Kafka text to read. His works never cease to beguile us. As the reader, you ask: What does he mean? What story is he telling? Yet at the same time, his works also provoke us, because he doesn’t give simple answers to these questions. And Kafka has a wonderful way of striking the perfect balance between the two – the question about meaning and refusing to give us the answer.

Oliver Jahraus holds the Chair of Contemporary German Literature and Media and is Vice President for Study and Teaching at LMU. His book Frank Kafka was recently published by reclam. Jahraus recommends The Metamorphosis – the first Kafka title he himself read many years ago – as a good place to get started.